How Does Tobacco/niccotine After Giving Birth Affect the Mom and Baby

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Health outcomes of smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period: an umbrella review

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth book 21, Commodity number:254 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Smoking during pregnancy (SDP) and the postpartum period has serious health outcomes for the female parent and infant. Although some systematic reviews have shown the bear upon of maternal SDP on particular conditions, a systematic review examining the overall health outcomes has not been published. Hence, this paper aimed to conduct an umbrella review on this outcome.

Methods

A systematic review of systematic reviews (umbrella review) was conducted according to a protocol submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42018086350). CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Spider web of Scientific discipline, CRD Database and HMIC databases were searched to include all studies published in English language by 31 December 2017, except those focusing exclusively on low-income countries. Two researchers conducted the study selection and quality assessment independently.

Results

The review included 64 studies analysing the relationship between maternal SDP and 46 wellness weather condition. The highest increase in risks was found for sudden babe death syndrome, asthma, stillbirth, depression nascency weight and obesity amongst infants. The impact of SDP was associated with the number of cigarettes consumed. Co-ordinate to the causal link analysis, five female parent-related and ten babe-related conditions had a causal link with SDP. In addition, some studies reported protective impacts of SDP on pre-eclampsia, hyperemesis gravidarum and skin defects on infants. The review identified of import gaps in the literature regarding the dose-response clan, exposure window, postnatal smoking.

Conclusions

The review shows that maternal SDP is not merely associated with short-term health weather (e.g. preterm nativity, oral clefts) but also some which can have life-long detrimental impacts (e.g. obesity, intellectual impairment).

Implications

This umbrella review provides a comprehensive analysis of the overall health impacts of SDP. The report findings signal that while estimating health and cost outcomes of SDP, long-term health impacts should exist considered equally well as short-term effects since studies not including the long-term outcomes would underestimate the magnitude of the issue. Also, interventions for significant women who smoke should consider the impact of reducing smoking due to health benefits on mothers and infants, and not solely cessation.

Background

Smoking during pregnancy (SDP) is a significant public health concern due to agin health outcomes on mothers and infants, such every bit miscarriage, depression birth weight (LBW), preterm birth, and asthma [ane,two,3,4]. The prevalence of SDP is around 10% in high-income countries (HICs) [5,half-dozen,seven] and 3% in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [viii].

Smoking during pregnancy generates a considerable price burden and the almanac cost of smoking-related pregnancy complications has been estimated to exist between £8 and £64 1000000 in the Uk, depending on the estimation method chosen [9]. In improver, the costs associated with the health problems experienced by the babe during the first year following the nativity were constitute to be between £12 and £23 million [nine]. Smoking during pregnancy poses a considerable economic burden in the USA every bit well, since smoking-owing neo-natal costs were estimated to be nearly $228 one thousand thousand in total [ten]. When long-term impacts on the infant are considered, the actual figures are likely to be higher. Therefore, to take a comprehensive estimate of the health and cost impacts of SDP to inform policy decisions and ensure that scarce health resources are allocated optimally, it is necessary to review the evidence on the overall health effects for mothers and infants over the longer term.

A scoping review and a review of reviews past Godfrey and colleagues [9], and a scoping review by Jones [11] provided a picture of the health and cost outcomes associated with SDP, and several narrative reviews about the wellness outcomes take been published [12,13,fourteen,15]. Nonetheless, none of these papers were fully systematic and comprehensive. Moreover, a considerable number of systematic reviews have been published more than recently on the bear on of maternal SDP on separate wellness outcomes, which makes this overall review of the current evidence timely.

The present study aimed to investigate the overall wellness impacts of maternal smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period on mothers and infants. Additionally, the evidence on the touch of the number cigarettes consumed and 2nd-manus smoking (SHS) past partner during pregnancy was assessed [sixteen, 17].

Methods

The guideline provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [18] was followed. The review was carried out co-ordinate to a protocol which included a detailed clarification of the methodology [19]. Umbrella reviews take been increasingly used to summarise the existing evidence on an consequence by analysing all systematic reviews conducted [18, 20]. Considering the large number of original studies nigh health outcomes of SDP, an umbrella review was the appropriate design for this enquiry.

Searches were undertaken of CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Spider web of Science, CRD Database (includes Dare, NHSEED and HTA) and HMIC databases. The search strategy for MEDLINE is presented in the Additional file one. All systematic reviews published in English and by Dec 2017. Two independent reviewers conducted the study selection and quality cess. The data extraction toll is provided in the Additional file ane: Table S1. The quality of included studies was assessed with a tool developed from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) checklist, which covers a range of issues including prior protocol use, bias in study selection, and consideration of publication bias and inclusion of a quality assessment [21]. Main outcome measures were odds ratios and relative risks for smoking women and their children compared to not-smoking women and their children.

To evaluate the causal link between SDP and the identified conditions which were found to have an clan with SDP, a causal link assay was conducted using established methods [11]. The evidence on the identified conditions was assessed and categorised using the following criteria:

-

Stiff evidence - one systematic review with ≥8 studies (group 1) or more than than one systematic review (group 2);

-

Weak testify – more than than i systematic review reported conflicting findings (grouping 3) or i systematic review reported limited number of studies (< 8) which establish a relationship (group 4).

A validity cess was conducted by reducing the threshold of 8 studies to seven, and increasing it to 10 and 12. Every bit discussed by Jones [eleven], this strength of evidence analysis fulfilled five of the ix items proposed past Hill [22] as weather of a causal link (strength, consistency, specificity, temporality, and plausibility). In addition, the dose-response clan was also considered. The remaining requirements (coherence, experiment, and analogy) of the Colina [22] criteria were irrelevant to this review as laboratory studies were non included and no causes other than smoking of the identified conditions were considered.

Results

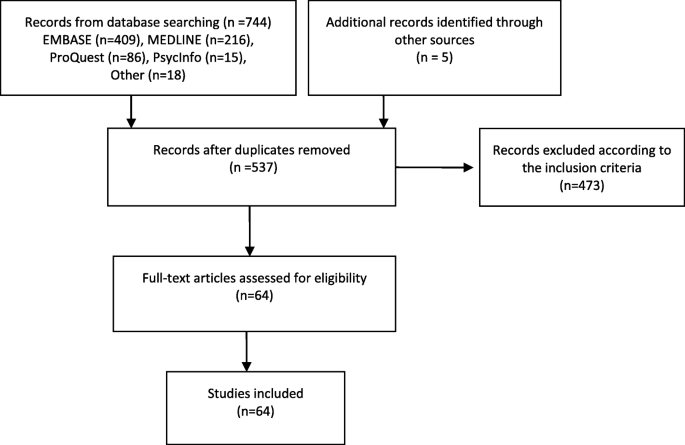

The database search yielded 744 studies and an additional five studies were establish through mitt searching the references of included studies. Post-obit the removal of duplicates and abstract screening, 64 studies were selected for full-text analysis Fig. one.

PRISMA Diagram for Study Selection

Characteristics of the included studies

Most reviews (northward = 46) were published since 2010. Only 13 reviews investigated a health condition related to mothers; the other 49 reviews analysed infant-related conditions, except ii [23, 24] which evaluated the impacts on both. Key characteristics of the included reviews are provided in Additional file ane: Table S2.

In most reviews (n = 27 reviews), the included studies were predominantly from HICs, and 22 of the included reviews covered studies from HIC only. In two reviews [three, 25] most of the included studies were concerned with upper-middle-income countries.

In 12 reviews, the country of focus of the included studies was not provided. All the same, one of them [26] conducted a meta-assay of the studies from Europe just, and in 5 reviews, the language of the included studies was either only English [27,28,29] or languages [30, 31] which are just spoken by HICs. In the remaining six reviews [32,33,34,35,36] at that place was no indication of whether the studies focussed on LMICs or HICs. Notwithstanding, when interpreting the results of these reviews, the possibility that studies which were conducted in LMICs take been included in addition to HICs should be born in mind.

Quality of the included studies

The quality scores of the reviews are provided in Additional file 1: Table S2. The highest achievable score was 16, and most reviews (n = 46) scored between nine and 14 while two reviews [25, 32] accomplished very low scores of four and 5. Therefore, nigh of the included reviews were moderate or high quality studies according to the criteria used.

Report choice was made by two reviewers independently in about half of the reviews (n = 31) to minimise bias. The bulk of the studies (n = fifty) assessed publication bias. Heterogeneity was measured in all reviews although causes of heterogeneity were not analysed in some (n = 17). Even so, only seven reviews reported protocol publication [iii, 26, 33, 37,38,39,40].

Impacts of smoking during pregnancy on mothers

Overall, of the 14 reviews that reported the impact of smoking on mothers, all except ii [41, 42] conducted meta-analyses (Boosted file one: Table S3). The reviews presented consistent findings, suggesting a significantly increased risk associated with smoking and seven health weather. The highest risks were reported for spontaneous miscarriage in assisted reproduction (OR = 2.65, 95% CI, i.33–5.30, 28) and ectopic pregnancy (OR = 2.thirty, 95% CI, 2.02–2.eighty, thirty). 2 conditions (preeclampsia and hypremesis gravidarum) were found to exist negatively associated with SDP. Hence, women who smoked whilst meaning were less likely to feel these two conditions.

Impacts of smoking during pregnancy on infants

Studies establish a smoking-related increased take a chance for 20 weather and the highest touch was observed for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (OR = 2.98, 95% CI, 2.51–iii.54) [24], asthma (OR = one.85, 95% CI, ane.35–2.53) [i], LBW (OR = 1.75, 95% CI, i.42–2.10), stillbirth (OR = 1.55, 95% CI, ane.36–1.78) [38] and obesity (OR = i.60, 95% CI 1.37–i.88) [43]. Studies did not notice whatsoever significant association betwixt fifteen conditions and SDP, including autism, brain tumors, breast cancer in daughters and testicular cancer in sons. On the other hand, a protective bear upon on skin defects was observed in one review [44].

Nearly studies (due north = 42) investigating the impacts of SDP on infants conducted a meta-analysis (Boosted file 1: Table S4), and only nine did not include this (Additional file i: Table S5). In these studies, there was no significant relationship between maternal SDP and lung functions, or Tourette'southward syndrome.

The age group of study participants varied between studies; for example, some weather condition were assessed amongst infants while some were measured in adults. In some reviews, participants were both infants and adults. Tabular array 1 lists health conditions by the life stage they were assessed.

The reviews included in this written report indicated that maternal smoking increased the take chances of death for the child during the prenatal menstruum, neonatal catamenia and infancy. The evidence showed maternal SDP did not only take curt-term impact but as well some long-term outcomes which could be detrimental for offspring. Moreover, some of the conditions measured in early life stages could continue after in life. For example, some birth defects and intellectual inability would affect later stages of life.

Dose-response association

To sympathize the impact of reductions in smoking, the relationship between the number of cigarettes consumed and the health implications for infants or mothers were investigated. Although a dose-response impact of SDP was reported in 27 reviews (22 related to baby atmospheric condition), it was statistically tested in but 17 studies. Amidst them, iv found no meaning bear on of SDP and their dose-response tests showed like results. In addition, one review [62] reported a dose-response association for SIDS but did not provide the odds ratios. Findings of the remaining 12 studies are summarised in the Additional file 1: Table S6.

To define low-cal, moderate and heavy smokers, most studies [38, 39, 46, 62,63,64] chose smoking ten cigarettes daily as a cut-off point to distinguish calorie-free smokers from moderate and heavy smokers. In some studies [4, 39, 46, 61, 64], both 10 cigarettes daily and 20 cigarettes daily were utilised as the thresholds. In ane review the number of cigarettes consumed daily for each category was inconsistent [65]. All studies estimated the risk ratios compared to non-smokers [66], except for one review, in which light smokers were compared to moderate smokers.

Included reviews showed that the risk of stillbirth, birth defects, preterm birth and perinatal expiry elevated equally the number of cigarettes increased [4, 38, 39, 46]. In contrast, smoking non only protected against pre-eclampsia simply the risk reduced as exposure increased [67].

A dose-response relationship was found in v reviews although a pooled interpretation was not calculated. They reported an increased take a chance for placental abruption [68], and for the offspring the take a chance of being overweight [57], having oral clefts [29, fifty], or a decrease in cerebral abilities [53] increased forth with the number of cigarettes that the mothers consumed. Five reviews included studies reporting a dose-response relationship forth with others that did not find any relationship [i, 41, 51, 56, 69]. Therefore, it was not articulate whether or not the risk for some atmospheric condition (pre-eclampsia, and in the offspring asthma, attention arrears hyperactivity disorder, and vision difficulties) was affected by the number of cigarettes consumed.

Six reviews observed no meaning clan between the number of cigarettes consumed and the risk of health conditions for the children exposed to maternal SDP, although overall they reported a significantly increased risk. These studies covered built heart diseases [65], central nervous organization tumors [64], childhood neuroblastoma [63], lower respiratory infections (LRI) [37] and lymphoblastic leukaemia [66], and reduced menarche age in daughters [61].

Impacts of postnatal maternal smoking on infants

The chief findings of the reviews which investigated the affect of postnatal smoking on the infants are shown in Boosted file 1: Table S7. The reviews showed an increased bear upon on asthma, LRI, SIDS and wheezing but not on leukaemia and obesity. Nevertheless, in some studies, information technology was not clear whether or not the mothers included in the studies smoked during the whole pregnancy equally well every bit the postpartum period. This is a meaning consideration as one study reported by Oken et al. [57] found no increase in the prevalence of obesity when the mother smoked only afterward birth, whereas smoking before and throughout pregnancy were found to be related with an increased risk [seventy].

Impact of second-mitt smoking by partners

In addition to active smoking, SHS during pregnancy could have wellness implications. It was of import to sympathize whether the health-related risks were higher when partners smoked during pregnancy. Therefore, partner-related findings of the included reviews were analysed. Partner smoking was considered in but 12 reviews of which half dozen did not assess the impact of SHS specific to the pregnancy period (Boosted file one: Tabular array S8). None of the studies reported the combined impact of SDP and SHS by the partner during pregnancy. Two reviews reported an increased hazard of SIDS [71] and delay in mental development [25] when the partners of non-smoking women smoked during pregnancy, while no clan was found for brain tumors [72] or breast cancer risk in daughters [73].

Sub-group analyses in the included reviews

The reviews conducted sub-grouping analyses to assess the touch of report pattern, sample size, the elapsing of the baby exposure to smoking (i.e. pre-pregnancy, first trimester or the whole pregnancy) and adjustments for confounding factors. The study findings did not differ significantly in about of the analyses except for adjustments for confounding and study quality. The evidence was not sufficient to make a comparing based on country income groups because nigh studies were from loftier-income countries.

Although the included meta-analyses utilised the nigh adapted estimations of observational studies when pooling their results, only 10 of the included reviews provided run a risk ratios for adjusted and unadjusted estimations (Boosted file 1: Tabular array S9). Studies with unadjusted ratios estimated greater values for miscarriage, perinatal death, SDIS, overweight and obesity.

Sub-grouping analyses based on quality appraisal of the included studies were conducted in 14 reviews (Additional file 1: Table S10). The results showed that high-quality studies reported higher ratios for some atmospheric condition (overweight, obesity, placenta previa) equally opposed to lower or insignificant ratios for some others (e.g. LBW, miscarriage, stillbirth).

Ii reviews [46, 74] compared the type of smoking status data and found similar results for biochemical and self-reported data. The exposure menstruation was researched in five reviews [40, 41, 46, 64, 75], and the results showed no pregnant difference between women who quit early in pregnancy and those who did not smoke.

Causal link analysis

The causal link assay identified a range of health conditions found to accept strong association with SDP; these are presented in Table ii, grouped according to the force of evidence.

Almost all of the conditions for which a strong association was identified fulfilled the criteria for a causal link. The health conditions were largely reported by moderate- or high-quality reviews and there were consistent findings in the sub-grouping analyses. There was not a sufficient biological explanation to the correlation found betwixt hyperemesis gravidarum and SDP, hence although there was a strong association, a causal link could not exist confirmed.

Discussion

This report analysed the health impacts of smoking during pregnancy and during the postpartum menstruation on mothers and infants. The 64 included reviews covered 1744 studies relating to SDP or smoking during the postpartum period. The review found that maternal SDP has curt-term and long-term health consequences, suggesting a positive association betwixt 20 babe-related and seven mother-related atmospheric condition, and a negative association with two maternal atmospheric condition. The review did not find a statistically significant impact of SDP on fifteen babe-related atmospheric condition while alien findings were reported for leukaemia and lymphoma.

The causal link analysis of the conditions that were establish to take an clan with SDP suggested that five female parent-related and 10 infant-related conditions had a causal link with SDP. PPROM and intellectual disability in children did not fulfil the criteria for the casual link although meta-analyses reported a statistically significant relationship with SDP.

Wellness conditions with alien results

Some health weather condition were assessed in multiple meta-analyses and they reported conflicting results. For instance, the increased adventure of having whatever type of nascence defect was statistically significant despite beingness small in the effect size (OR = 1.18, 95% CI, ane.14–one.22) in one review [39] as opposed to a borderline ratio (OR = one.01, 95% CI, 0.96–ane.07) reported in some other [44]. The main divergence was the reduced risk of pare defects (OR = 0.82, 95% CI, 0.75–0.89) which was included in the latter [44] while omitted in the old [39] without any justification. All v studies included in this meta-analysis reported a negative relationship and the heterogeneity was low (P = 0.00001, I2 = 0%). Therefore, the show suggested an increased run a risk of birth defects except for skin defects amidst SDP exposed children. Nevertheless, there was no biological explanation for the potential protective touch of SDP on skin defects.

Some other health condition with mixed findings was leukaemia. I meta-analysis [64] including 19 studies indicated an insignificant decreased risk (OR = 0.99, 95% CI, 0.92–i.06) whereas another review [66] of 21 studies found an increased gamble (OR = 1.10, 95% CI, i.02–1.19). The difference could exist explained past the dissimilar studies included, since there were only five studies mutual to both, and the clan between SDP and leukaemia is unclear.

Similarly, the reviews reported different results for lymphoma. 1 meta-assay [55] found an insignificant association between any lymphoma and SDP based on eight studies (OR = 1.10, 95% CI, 0.96–1.27), although positive human relationship for non-Hodgkin lymphoma was reported (OR = 1.22, 95% CI, 1.03–1.45, north = eight). Some other review [64] which included six studies establish an increased risk for any lymphoma (OR = 1.21, 95% CI, 1.05–one.34). Hence, SDP increases the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma just for other types of lymphoma the impact is unclear.

Strengths and limitations of the umbrella review

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first umbrella review on the topic and provides the most systematic and comprehensive assessment of the current evidence. The criteria to assess any causal links are an important consideration. The tool developed by Hill [22] is widely recognised for assessing causation. In add-on to these criteria, this study considered the quality of reviews and the findings of sub-group analyses. Hence, the weather identified by the causal link analysis are very likely to have a causal link with SDP.

The review has some limitations. Firstly, although systematic reviews are accepted equally the highest in the evidence hierarchy [76, 77], the focus on systematic reviews solitary meant some health conditions were not covered. Some original studies take indicated the touch of SDP on other baby-related atmospheric condition, such as diabetes [78], hypomania [79], otitis [lxxx] and pervasive development disorder [81], which were not assessed in a systematic review, and as a result were not included in this study. Furthermore, SDP has been shown to be related to the smoking uptake of the offspring [82, 83]. At that place are too some maternal health weather found to exist related to smoking whilst pregnant in 1 study; vein thrombosis, myocardial infarction, flu or pneumonia, bronchitis, gastrointestinal ulcers [84]. Notwithstanding, the electric current study focused on the conditions for which at that place was strong prove from systematic reviews.

The methodological limitations of the original studies covered in the included reviews should be born in mind when interpreting the results of the electric current review. Outset, long-term implications of SDP were often tested retrospectively by asking mothers whether or non they had smoked during pregnancy. This clearly has limitations as these studies were not designed to compare the offspring of smoking mothers with the children of not-smoking mothers to determine differences in their health, but rather to compare the exposure in children with particular conditions and those without these conditions. The second issue is the usual reliance on mother's memory and openness about their smoking behaviour is unsatisfactory. The tertiary issue is the touch of misreckoning factors. For example, a 7-yr-old child with diagnosed asthma could have a mother who smoked during pregnancy simply and a father who smoked during pregnancy and the postpartum period. To minimise the impact of this the most adjusted estimations were reported in this review.

The review in the context of literature

Two previous scoping reviews were conducted to define the health outcomes of SDP although they did non focus on systematic reviews [9, 11]. The scoping review past Jones et al. [xi] was more comprehensive and included 32 health weather. A quality cess was not conducted just specific criteria were used to assess the forcefulness of the testify. According to the criteria, Jones et al. suggested that the evidence for a link between obesity and SDP was non strong [11]. Withal, the electric current analysis suggests a causal link due to the inclusion of two subsequently published systematic reviews [32, 43].

Some of the wellness conditions covered in this study were too included in the review by Godfrey et al. merely often college ratios were reported [9]. This might be because they included narrative reviews which did not split maternal SDP and postnatal passive fume exposure while estimating the summary risk ratios [24, 85,86,87]. Moreover, none of the previous reviews analysed the impact of the number of cigarettes consumed, partners' smoking and postpartum smoking on infants. Therefore, the current review is more comprehensive and more than systematic than previous studies.

Gaps in the literature

The study identified important gaps in the literature which warrant further research. In item, there is a need to further our understanding of dose-response clan, the bear upon of postnatal smoking, and SHS during pregnancy. Current evidence on the affect of number of cigarettes consumed suggests that even low amounts of cigarette consumption during pregnancy take significant health outcomes and there is a clear slope for some weather condition. This indicates the importance of smoking abeyance during pregnancy and if reduction in smoking which is oft not addressed in smoking cessation interventions designed for meaning women.

Only two studies assessed the impact of SHS by partners during pregnancy when the mother was a not-smoker. In that location was no review reporting the combined impact of SDP and SHS by partners during pregnancy while two reviews reported increased risks for SID [43] and delay in mental development [25] when but the partner smoked during pregnancy. Hence, more research is needed to sympathise the impacts of having a smoking partner during pregnancy.

Conclusion

This study has shown that smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period has pregnant health consequences for mothers and infants. It is important to encourage meaning smokers to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes consumed if they are not prepared to quit entirely since the existing evidence indicates a dose-response association. Similarly, the bear upon of SHS needs to be considered to promote a smoke-free environment for the female parent and baby.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SDP:

-

Smoking during pregnancy

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

- LRI:

-

Lower respiratory infections

- HICs:

-

Loftier-income countries

- LMICs:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- CRD:

-

Eye for Reviews and Dissemination

- SHS:

-

Second-mitt smoking

- SIDS:

-

Sudden babe death syndrome

References

-

Burke H, Leonardi-Bee J, Hashim A, Pine-Abata H, Chen Y, Melt DG, et al. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and Meta-assay. Pediatrics. 2012;129(four):735–44. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2196.

-

Castles A, Adams EK, Melvin CL, Kelsch C, Boulton ML. Effects of smoking during pregnancy. Five meta-analyses. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(iii):208–15. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0749-3797(98)00089-0.

-

Pereira PP, Da Mata FA, Figueiredo AC, de Andrade KR, Pereira MG. Maternal active smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight in the Americas: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(5):497–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw228.

-

Shah NR, Bracken MB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies on the association between maternal cigarette smoking and preterm commitment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(2):465–72. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0002-9378(00)70240-seven.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Commonwealth of australia'southward mothers and babies 2015. Canberra: AIHW; 2017.

-

NHS. Statistics on Smoking. England: NHS; 2017.

-

Tong VT, Dietz PM, Farr SL, D'Angelo DV, England LJ. Estimates of smoking earlier and during pregnancy, and smoking cessation during pregnancy: comparing two population-based data sources. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC : 1974). 2013;128(3):179–88.

-

Caleyachetty R, Tait CA, Kengne AP, Corvalan C, Uauy R, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB. Tobacco utilize in pregnant women: analysis of data from demographic and health surveys from 54 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(9):e513–e20. https://doi.org/x.1016/S2214-109X(14)70283-9.

-

Godfrey C, Pickett KE, Parrott Due south, Mdege ND, Eapen D. Estimating the costs to the NHS of smoking in pregnancy for meaning women and infants. York: Academy of York; 2010.

-

CDC. Annual Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Years of Potential Life Lost, and Economical Costs, Us. 2002.

-

Jones M. The development of the economic impacts of smoking in pregnancy (ESIP) model for measuring the impacts of smoking and smoking cessation during pregnancy: Academy of Nottingham; 2015.

-

Banderali Chiliad, Martelli A, Landi M, Moretti F, Betti F, Radaelli Thousand, et al. Short and long term wellness effects of parental tobacco smoking during pregnancy and lactation: a descriptive review. J Transl Med. 2015;xiii(1):327. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-015-0690-y.

-

Bruin JE, Gerstein HC, Holloway Ac. Long-term consequences of fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure: a critical review. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116(2):364–74. https://doi.org/ten.1093/toxsci/kfq103.

-

Delpisheh A, Brabin L, Brabin BJ. Pregnancy, smoking and nascence outcomes. Women Health. 2006;2(3):389–403. https://doi.org/10.2217/17455057.2.3.389.

-

Cnattingius Due south. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: Smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl_2):S125–S40.

-

Overnice. Smoking: stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth (PH26). NICE; 2010.

-

Baxter S, Blank Fifty, Guillaume L, Messina J, Everson-Hock E, Burrows J. Systematic review of how to end smoking in pregnancy and following childbirth: University of Sheffield; 2009.

-

Higgins J, Light-green Southward. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. Wiley-Blackwell: England; 2011.

-

Saygın Avşar T, McLeod H, Jackson L. Health outcomes of maternal smoking during pregnancy and postpartum period for the mother and infant: protocol for an umbrella review. Syst Rev. 2018;vii(1):235. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0900-9.

-

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid-Based Health. 2015;thirteen(3):132–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055.

-

CRD. CRD'south guidance for undertaking reviews in health care: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Academy of York; 2009.

-

Hill AB. The surroundings and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58(5):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591576505800503.

-

Jayes L, Haslam PL, Gratziou CG, Powell P, Britton J, Vardavas C, et al. SmokeHaz: systematic reviews and Meta-analyses of the effects of smoking on respiratory health. Chest. 2016;150(1):164–79. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.chest.2016.03.060.

-

Difranza JR, Lew RA. Consequence of maternal cigarette-smoking on pregnancy complications and sudden-baby-death-syndrome. J Fam Pract. 1995;twoscore(four):385–94.

-

Tsai MS, Chen MH, Lin CC, Ng S, Hsieh CJ, Liu CY, et al. Children's environmental health based on nascency cohort studies of Asia. Sci Total Environ. 2017;609:396–409. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.081.

-

Kantor R, Kim A, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(half-dozen):1119–25.e1.

-

Latimer K, Wilson P, Kemp J, Thompson 50, Sim F, Gillberg C, et al. Disruptive behaviour disorders: a systematic review of environmental antenatal and early years gamble factors. Child Care Wellness Dev. 2012;38(five):611–28.

-

Waylen AL, Metwally 1000, Jones GL, Wilkinson AJ, Ledger WL. Effects of cigarette smoking upon clinical outcomes of assisted reproduction: a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(1):31–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmn046.

-

Xuan Z, Zhongpeng Y, Yanjun G, Jiaqi D, Yuchi Z, Bing Due south, et al. Maternal active smoking and risk of oral clefts: a meta-assay. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(six):680–90. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.oooo.2016.08.007.

-

Ankum WM, Mol BWJ, Van der Veen F, Bossuyt PMM. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-assay. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(6):1093–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(sixteen)58320-4.

-

Chao TK, Hu J, Pringsheim T. Prenatal risk factors for tourette syndrome: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):53.

-

Huang JS, Lee TA, Lu MC. Prenatal programming of childhood overweight and obesity. Matern Kid Health J. 2007;11(5):461–73.

-

Huncharek MS, Kupelnick B, Klassen H. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the chance of childhood brain tumors: a meta-analysis of 6566 subjects from twelve epidemiological studies. J Neuro-Oncol. 2002;57(1):51–7. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015734921470.

-

Ferrante G, Antona R, Malizia 5, Montalbano 50, Corsello M, La Grutta S. Fume exposure every bit a gamble cistron for asthma in childhood: a review of electric current evidence. Allergy Asthma Go on. 2014;35(6):454–61. https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2014.35.3789.

-

Little J, Cardy A, Munger RG. Tobacco smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Balderdash Globe Health Organ. 2004;82(3):213–viii.

-

Tuomisto J, Holl Grand, Rantakokko P, Koskela P, Hallmans G, Wadell Thou, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and testicular cancer in the sons: a nested case-control study and a meta-assay. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(9):1640–viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.017.

-

Jones LL, Hashim A, McKeever T, Melt DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental and household smoking and the increased gamble of bronchitis, bronchiolitis and other lower respiratory infections in infancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2011;12:i. https://doi.org/x.1186/1465-9921-12-5.

-

Marufu TC, Ahankari A, Coleman T, Lewis S. Maternal smoking and the take a chance of still nascency: systematic review and meta-assay. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):239. https://doi.org/x.1186/s12889-015-1552-v.

-

Nicoletti D, Appel LD, Siedersberger Neto P, Guimaraes GW, Zhang Fifty. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and nascency defects in children: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cadernos de saude publica. 2014;30(12):2491–529. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00115813.

-

Wendland EM, Pinto ME, Duncan BB, Belizán JM, Schmidt MI. Cigarette smoking and risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review of observational studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-8-53.

-

England L, Zhang J. Smoking and chance of preeclampsia: a systematic review. Front Biosci. 2007;12(1):2471–83. https://doi.org/10.2741/2248.

-

Lancaster CA, Gilded KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(i):5–14. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.007.

-

Riedel C, Schonberger Thousand, Yang Due south, Koshy M, Chen YC, Gopinath B, et al. Parental smoking and childhood obesity: higher consequence estimates for maternal smoking in pregnancy compared with paternal smoking--a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1593–606. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu150.

-

Hackshaw A, Charles R, Sadie B. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review based on 173 687 malformed cases and 11.seven meg controls. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(5):five.

-

Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Froen J, Smith GC, Gibbons Chiliad, et al. Major gamble factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331–40. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7.

-

Pineles BL, Hsu S, Park E, Samet JM. Systematic review and Meta-analyses of perinatal death and maternal exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(2):87–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv301.

-

Chrestani MA, Santos IS, Horta BL, Dumith SC, de Oliveira Dode MA. Associated factors for accelerated growth in childhood: a systematic review. Matern Child Wellness J. 2013;17(three):512–nine. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10995-012-1025-8.

-

Lee L, Lupo P. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of congenital centre defects: a systematic review and a meta-assay. Circ Conf. 2012;125(10 SUPPL. 1):398.

-

Wang M, Wang ZP, Zhang M, Zhao ZT. Maternal passive smoking during pregnancy and neural tube defects in offspring: a meta-assay. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(three):513–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-2997-three.

-

Wyszynski DF, Duffy DL, Beaty Th. Maternal cigarette smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997;34(iii):206–10. https://doi.org/10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0206_mcsaoc_2.iii.co_2.

-

Zhang D, Cui H, Zhang Fifty, Huang Y, Zhu J, Li X. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy associated with an increased risk of congenital eye defects amidst offspring? A systematic review and meta-assay of observational studies. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(6):645–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1183640.

-

Brion Thou-JA, Leary SD, Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Ness AR. Modifiable maternal exposures and offspring blood pressure: a review of epidemiological studies of maternal age, diet, and smoking. Pediatr Res. 2008;63(6):593–eight. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816fdbd3.

-

Clifford A, Lang L, Chen R. Effects of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy on cognitive parameters of children and young adults: a literature review. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2012;34(6):560–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2012.09.004.

-

Ino T. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring obesity: Meta-assay. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(1):94–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02883.ten.

-

Antonopoulos CN, Sergentanis TN, Papadopoulou C, Andrie E, Dessypris Due north, Panagopoulou P, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood lymphoma: a meta-assay. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(11):2694–703. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25929.

-

Linnet KM, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, Wisborg Thousand, Henriksen TB, Rodriquez A, et al. Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy take chances of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: review of the current evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1028–40. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1028.

-

Oken E, Levitan Due east, Gillman Thou. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2008;32:10.

-

Rayfield S, Plugge East. Systematic review and meta-assay of the association betwixt maternal smoking in pregnancy and childhood overweight and obesity. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2017;71(ii):162–73. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207376.

-

Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, Yang Yard, Glazebrook CP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(12):1019–26. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-302263.

-

Huang J, Zhu T, Qu Y, Mu D. Prenatal, perinatal and neonatal take chances factors for intellectual inability: a systemic review and meta- Assay. PLoS I. 2016;eleven(iv):e0153655.

-

Yermachenko A, Dvornyk V. A meta-analysis provides evidence that prenatal smoking exposure decreases age at menarche. Reprod Toxicol. 2015;58:222–8. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.reprotox.2015.x.019.

-

Zhang K, Wang X. Maternal smoking and increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-assay. Legal Med (Tokyo, Japan). 2013;xv(3):115–21.

-

Chu P, Wang H, Han S, Jin Y, Lu J, Han W, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of childhood neuroblastoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(2):999.

-

Rumrich IK, Viluksela M, Vahakangas G, Gissler 1000, Surcel HM, Hanninen O. Maternal smoking and the risk of cancer in early on life - a meta-assay. PLoS 1 [Electronic Resource]. 2016;eleven(xi):e0165040.

-

Lee LJ, Lupo PJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of congenital center defects in offspring: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34(ii):398–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-012-0470-x.

-

Yan K, Xu 10, Liu X, Wang X, Hua S, Wang C, et al. The associations betwixt maternal factors during pregnancy and the run a risk of childhood astute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis.[erratum appears in Pediatr blood Cancer. 2016 may;63(5):953-4; PMID: 26999072]. Pediatr Claret Cancer. 2015;62(vii):1162–seventy. https://doi.org/x.1002/pbc.25443.

-

Conde-Agudelo A, Althabe F, Belizan JM, Kafury-Goeta Air conditioning. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy and run a risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(4):1026–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70341-8.

-

Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Incidence of placental abruption in relation to cigarette smoking and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(four):622–viii. https://doi.org/x.1016/s0029-7844(98)00408-vi.

-

Fernandes Thou, Yang X, Li JY, Cheikh IL. Smoking during pregnancy and vision difficulties in children: a systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(3):213–23. https://doi.org/ten.1111/aos.12627.

-

Toschke AM, Beyerlein A, von Kries R. Children at loftier chance for overweight: a classification and regression trees analysis approach. Obes Res. 2005;xiii(7):1270–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2005.151.

-

Mitchell EA, Milerad J. Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome. Rev Environ Health. 2006;21(2):81–103. https://doi.org/x.1515/reveh.2006.21.ii.81.

-

Huang Y, Huang J, Lan H, Zhao G, Huang C. A meta-analysis of parental smoking and the risk of childhood brain tumors. PLoS One. 2014;ix(7):e102910.

-

Park SK, Kang D, McGlynn KA, Garcia-Closas G, Kim Y, Yoo KY, et al. Intrauterine environments and chest cancer risk: meta-assay and systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(1):R8. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1850.

-

Jones LL, Hassanien A, Melt DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental smoking and the risk of eye ear affliction in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(one):18–27. https://doi.org/x.1001/archpediatrics.2011.158.

-

Pineles BL, Park Eastward, Samet JM. Systematic review and Meta-assay of miscarriage and maternal exposure to tobacco fume during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(7):807–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt334.

-

Evans D. Hierarchy of evidence: a framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00662.10.

-

Murad MH, Asi Northward, Alsawas One thousand, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016;21(4):125–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401.

-

Montgomery SM, Ekbom A. Smoking during pregnancy and diabetes mellitus in a British longitudinal birth accomplice. Br Med J. 2002;324(7328):26–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7328.26.

-

Mackay DF, Anderson JJ, Pell JP, Zammit S, Smith DJ. Exposure to tobacco smoke in utero or during early babyhood and risk of hypomania: prospective birth cohort report. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;39:33–9. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.06.001.

-

Haberg SE, Bentdal YE, London SJ, Stigum H, Kvaerner KJ, Nystad W, et al. Pre- and postnatal parental smoking and acute otitis Media in Early Babyhood. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2009;179:one.

-

Tran PL, Lehti V, Lampi KM, Helenius H, Suominen A, Gissler M, et al. Smoking during pregnancy and gamble of autism spectrum disorder in a Finnish National Nascency Cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27(iii):266–74. https://doi.org/ten.1111/ppe.12043.

-

Biederman J, Martelon M, Woodworth KY, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for cigarette smoking in offspring? A longitudinal controlled study of ADHD children grown up. J Atten Disord. 2017;21(12):975–85. https://doi.org/ten.1177/1087054714557357.

-

Niemela South, Raisanen A, Koskela J, Taanila A, Miettunen J, Ramsay H, et al. The effect of prenatal smoking exposure on daily smoking amid teenage offspring. Habit. 2016;112(ane):134–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/add together.13533.

-

Roelands J, Jamison MG, Lyerly Advertisement, James AH. Consequences of smoking during pregnancy on maternal health. J Women'south Health. 2009;18(half-dozen):867–72. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2008.1024.

-

Andres RL, Day K-C. Perinatal complications associated with maternal tobacco employ. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5(3):231–41. https://doi.org/10.1053/siny.2000.0025.

-

Salihu HM, Wilson RE. Epidemiology of prenatal smoking and perinatal outcomes. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(11):713–twenty. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.08.002.

-

Walsh RA, Redman Southward, Brinsmead MW, Byrne JM, Melmeth A. A smoking cessation program at a public antenatal clinic. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(7):1201–4. https://doi.org/x.2105/AJPH.87.7.1201.

Funding

No funding was received specifically for this review. Information technology was conducted every bit role of the lead writer's PhD inquiry at the University of Birmingham, which was funded by the Turkish Ministry of Pedagogy. Hugh McLeod's time is supported by the National Institute for Wellness Research Applied Research Collaboration West (NIHR ARC West) at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

The search strategy was developed past the research team. TSA conducted the review, analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. Second reviewing was done by HM and LJ. HM and LJ provided inputs in analysing the information and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and point if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If material is non included in the article's Artistic Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/) applies to the information made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the information.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avşar, T.Due south., McLeod, H. & Jackson, Fifty. Health outcomes of smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period: an umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 254 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03729-one

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03729-1

Keywords

- Smoking during pregnancy

- Partner smoking

- Systematic review

- Umbrella review

- Health outcomes

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-021-03729-1

0 Response to "How Does Tobacco/niccotine After Giving Birth Affect the Mom and Baby"

Post a Comment